Architecture education, architectural design, media, and digital fabrication—these domains, though part of a cohesive system, often appear disconnected from one another. The gap between architectural education and practical reality widens due to the constraints of traditional mediums and tools. While education claims to prepare future architects, students may spend decades achieving professional competence. The tools and media at their disposal lead many architects to view theory and practice as separate entities—as distinct from each other as science fiction is from actual construction. In the realm of theory, architectural research may be enigmatic and impressive, yet it’s often confined by the mediums of drawing and rendering and by the modes of presentation. The architect, therefore, risks becoming a “Drawing-tect,” with the primary objective of producing aesthetically pleasing drawings. This issue is even more pronounced in the educational sphere, where considerations of actual space are secondary until one enters the professional field. In contrast, practitioners in digital experiences and fabrication have recognized these inherent limitations and are rapidly advancing towards tangible experiences and outcomes. Architectural education, isolated from spatial practice by limited media, must question what remains at its core beyond the act of drawing.

Catalogue

The Power of Architects

The Medium of Architects

Topics by Architects

The Future of Spatial Narrative

The Power of Architects

Architects often command a certain prestige in the public eye, perceived as key figures in shaping our built environment and wielding the power to realize their own visions. However, the reality of the architect-client-user triad is more complex. Architects typically serve the client, who funds the construction, rather than the end-user—except in the case of private residences. Within this dynamic, presentations become a crucial arena for architects to advocate for their designs, where statistics and effects are manipulated to substantiate their proposals.

A latent tension exists within architects; a resistance to outcomes that deviate from their initial simulations. There’s a reluctance to relinquish control over the experience, a fear of being unable to justify their choices should the results shift beyond their direct influence. This concern is amplified when outcomes dynamically respond to the user in real-time, independent of the architect’s predetermined renderings. No matter the eloquence or grandeur with which they discuss their concepts, they may find their work marginalized if it cannot adapt to live interaction.

Architects often present their work from a removed standpoint, dictating perspectives and experiential pathways, sometimes resorting to illusion to persuade their audience. This common approach underscores a broader issue within the profession: an inherent distance from the tangible, lived experiences their creations are meant to foster.

Let’s make a comparison:

■ For architecture education: “eating an apple is good tho, but not complex enough” Analysis and description over an apple is always the top concern. Only when you show a diagram to architects, to describe the flavor of an apple, they will be satisfied and excited. Upon a single apple, an architect may show you a bunch of sections. As for drawing technics for these sections, a long article is inevitable and they will also refer to “apple sections” by colleagues. Of course, they will talk about how this apple relates to society and philosophy.

■ For professional architects: architect will not take apple to the presentation, and this apple tree needs to be planted. In some conditions, there will be a bunch of statistics and analytics about apple, and even this apple can be described as pear flavor. But once audiences want to taste it, they will need to pay for the descriptions. If the result is different, the only thing to blame is the execution process – at least architect thinks so. How close is the result similar to description? Well, that depends on professional experience of architects, and how responsible they are – anyway, being “edible” is the bottome line.

■ For digital fabricators: designer will constantly try how to grow the best apple with the least cost or shortest time. They will also try growing “lemon-shape-apple” or “meat-flavor-apple”, even growing red apple with green apple. Designer will bring the product and ask consumer to taste. Consumer can comment on the apple and the designer cannot defend.

■ For medium related practitioners: designers will use new technology to simulate an apple for consumer, or let them choose what fruit they want to taste. In some conditions, designer can even simulate a non-existing fruit, or make you feel like an apple.

Architectural education is efffected by the nature of architecture profession (architects are not responsible to users, and they need to convince client to build their project). What architecture school provides, is still education of drawing and image – which requires architect to produce a set of drawing over a non-existence, and make audiences to imagine the experience, then finally, pay for it. Meanwhile, when producting the result is totally feasible, architect will still define drawings and diagrams as the goal of production. This also makes architectural presentation confusing on simple issues.

Architecture Drawing created language for architects, but also split education away from practice. As production is based on an inaccessible “plan”, architect will discuss inaccessible issues, getting away from what they can do, from those non-architectural-design practices – which is probably more feasible, such as digital fabrication and interactive design. By contrast, architectural education always use limited non-practice fantasies to deal with reality, , though they appears to be architectural, even architectural design.

For instance, almost all architecture schools cater to COVID-19, expecting to use material architecture to “do something”. Or in another word, they only practice on material world, undermining the power of virtuality(though we have seen many architects exploring on virtual space, but they almost stop at diagram stage, instead of “doing” practice on making systems and frameworks). A probably reason is the “architect-client-user” system has trained architects’ mind, that PRACTICE is DOING LIP SERVICE which is NOT EVEN VALIDATED. While discussing big topics, architects just release some “PLAN“, and sime “DIAGRAM” – then, STOP, unless somebody is convinced to pay. We have to admit, what “architecture practice” can do is quite limited. Architects work tough on its own, but expecting to have influence on other fields, with “architecture practice”. It is not hard to say, how many such “practices” had become a mere imagination, like those “unlisted” projects. The funny thing is that, though tools we have today, totally allow us to validate our ideas (such as interactive media), these virtual practitioners are still the minority. In fact, a linear prediction under architectural/academic mindset will probably not work the same as we expect. The most worrying of all is that, ALMOST ALL ARCHITECTS WORK THIS WAY – WHY DONT WE DO WHAT WE CAN DO? OR ANYTHING ACCESSIBLE? Architects discuss what is architecture, but hardly discuss proficient way of production, which was even not defined as “architecture”.

We have to admit that, architectural mindset is efficient and advanced in prediction and setting up plans – but, exactly because of that, architectural predictions shall not, and are not able to “PREDICT NOW” – which is literally a paradox. Using material architecture to reflect now, can never catch up to the rapidly changing world, inherently ignoring circumstances. In fact, to reflect now, to reflect what public expecting to experience, we need to totally shift our mind and medium, and change the way we run projects. For example, larning from fields who has further influence over society/culture/public – such as art, entertainment and gaming, which address result and user experience. But for architectural education and most architects, it’s drastically difficult to step out of the mindset and comfort zone.

There’s a myth in architecture, especially in education that – ” I’m using image to express idea over material world. I believe that is feasible practice, even it is actually not feasible!” Though in fact, there are many “non-practice” medium, which has more concern over humanity and user, but drawings and images are still regarded as the most praised language – “ARCHITECTS DO DRAWINGS!” Even when architect discuss these media, they use drawings. Even though architects are quite clear that, the day these projects being constructed, may never come. Even these drawings cannot be anything except drawing or architecture. Architects are never tired of this – where they base on, the ART OF DRAWING.

The Medium of Architects

Mediums used by architects are generally mysterious and distant, from audience and user experiences. Under such condition, ideas are ruled by architects, which cannot be examined. The fact is that, what drawing describes, is never compatible with an experiential result. Just like a language, it defines a specific set of rules and user group, which is not understandable by others. In some cases, these architectural language are only feasible in drawings, rather than for validated results. Nothing will be delivered to audiences/users.

Architectural mediums are distant, in time. For instance, digital fabrication validates ideas through precise simulation and tests, meanwhile, architecture construction needs to go through long-long stages of report, construction drawing and visits. As a result, these two practice requires different tools and different efficiencies. What digital fabrication doing is, reaching the result as soon as possible, with any accessible resources. Meanwhile, speed is not a matter of concern in architectural design. Former one is “do it” then “what you see is what you get”, the later one is giving instruction and the construction heavily rely on client and constructor.

The distant of medium is related to the distant time. While audiences see a digital fabricator only showing images, they will strongly urge for a result. While they are listening to an architectural report, they will only comment on images shwon by architects. – because the construction never rely on architects. Mediums used by architectural education, was originally developed from professional drawings. As a consequence, architects who are trained in this way, hardly consider whether the rules they set up can be logically constructed or experienced in the end. They care more about whether “description” of these rules can be literally understood-which is probably a good way to convince somebody with nothing in hand. In professional architecture world, urged by responsibilities in construction, architects will be more and more proficient in prediction and description. By constrast, in education/pre-professional system, we lost the destination, or to say, the construction/result. As a consequence, the more we stress “drawing abilities”, the further we are away from practice. Especially when people do “conceptual drawings”, which is merely drawing, the more sophisticated it is, the more it gets away from reality, from construction, from experience, which is even not logically functioning. Such act is extremely irresponsible for the actual users and audiences.

In practical projects, under the pressure of corresponding construction responsibilities, an architect’s predictive and expressive abilities will progressively improve. In contrast, in architectural education, the lack of a definitive endpoint means the more we emphasize training in drawing, the more counterproductive the results become. The non-precise drawings (beyond those that concretely express structure or experience) become more exquisite, the final outcome deviates further from the construction phase and architectural practice. This can also be seen as extremely irresponsible towards the actual users and experiencers of the space. Compared to these architectural images, content that is more easily understood by audiences and focuses on the human perspective and experience is, in fact, closer to architectural practice (perhaps these contents reduce the complexity and mystique of rule interpretation for architects and do not highlight the architect’s image construction ability, but undoubtedly, the results are beneficial).

This is perhaps easily understood by those frequently engaged in real-time interaction, but for architects, particularly architectural researchers, the importance of outcomes is often not recognized. Most of the architect’s work stops at the planning—”plan”—stage, and the implementation of the plan is left to others. This leads to architects essentially being responsible for drawing only; the commonly used term “representation” reflects the detachment of drawing. Research based on drawing can only ever “represent” something and cannot bring it to fruition. At the same time, for architects, overlooking the thing itself has become a habitual way of thinking. Of course, this relates to the architect’s former mode of work—when envisioned content is unattainable and requires convincing others to help realize it, making a plan look perfect becomes paramount.

An undeniable fact is that the various mapping and drawing techniques architects favor are just one way of presenting, but they are often mythologized or can be “praised” as “the art of drawing,” divorced from the subject of discussion. Although these non-precise drawings often acquire a painting-like aesthetic appeal after processing and can be inspiring in their inaccurate depiction of things, such visual information is still limited to a single static frame and is merely “good-looking.” Objectively, even a built structure is interactive, real-time, and from a human perspective, yet architectural drawing limits thinking to static content.

Drawings by Daniel Libeskind

Architectural drawing presenting as fancy painting. What does it mean to public? Maybe nothing more than some painting or blueprints.

It is regrettable that the education and evaluation system in architecture, rooted in the significance of drawings, has become entrenched. The quality of drawings, even deceptive ones, directly dictates the assessment of a design. Admittedly, these skills are very necessary during presentations, and showcasing plans is a crucial ability, but it is not the only job and should not be at the expense of others. These skills are commonly used by architects to persuade, because of the arbitrary nature of their rules, which is also the only area where architects can defend themselves. However, these seemingly rational diagram analyses often cannot accurately represent spatial experiences, and their flaws are ignored, which is a disaster for users and experiencers. Apart from the exhibition phase often isolated by architects, other drawings and thought processes rarely truly design from a human perspective. Although new media and methods have already allowed us to move forward, inertia still causes most people to view them merely as a means of producing static images (here, static broadly refers to unidirectional output of static content, such as using interactive media for visualization and rendering films, producing content that cannot be changed in real-time by users or designers, i.e., users do not have the right to define).

The limitations of media have led to a misalignment in architectural education and a growing rift with practice. Drawing, as a long-standing important expression for architects, has begun to hinder the development of architectural and spatial design. As a discipline based on “hypotheses,” architects are unable to validate their design content and receive feedback to calibrate their judgment until they have sufficient resources. This leads to a very long growth trajectory for architects, where experience accumulates very slowly. A non-architectural designer can get practical opportunities or even start their own studio shortly after leaving the educational system, while architects often need many years, if not decades. The difficulty of practice is undeniable, but beyond designing a building, there are many more paths to practice, and existing media have provided more ways. This is already old news in the direction of interaction and digital construction. On the other hand, not doing buildings, but practicing from the aspect of spatial experience or specific construction, often leads to more significant changes. Although practitioners of digital construction and interactive space are increasing, we still need more people to join in.

Architects’ Topics

The topics discussed in architecture are never limited to the physical entity of buildings. They extend outward, adeptly transforming concepts from other fields for their use, which is commendable. In terms of interdisciplinarity and cross-specialization, architecture has been interdisciplinary since its inception—on the practical side, as a carrier of daily production and life, we have countless types of needs for it; on the theoretical side, architecture cannot talk to itself nor can it be self-sufficient just by its theories (one of the reasons is, if we remove the “borrowed” parts from architectural theory, and the parts related to practical theory, what remains mostly comes from the defenses made by a “master architect” for their own schemes decades or even centuries ago). In this environment, the topics of architects are becoming broader, and the envisioned time scales vary, which is when architects need to actively explore outward and truly understand what is happening in other industries.

Before that, we first need to recognize the limitations of existing thinking:

- Architecture is keen on using visualization and form generation to discuss everything. Not just in architecture, but visualization and form generation thinking is a set pattern in design and art industries. For example, designers tend to convert a sound/taste/touch into a specific visual form (spectrum, color, sculpture, etc.) and treat the visual form as the sole content of their work, rarely discussing from the sensation itself, but the good-looking results are meaningless for the senses themselves. Personally, I do not believe there is any necessary connection between these information transformations. Our different senses process information differently, and the interpretation and feeling of this information are more linked to personal experience, which varies from person to person. (The real connection is the timing and intervals of changes, the visual aspect of music and its connection is precisely because the peaks and troughs of these two senses synchronize over time. Just like the specific colors in thermal imaging can be any gradient mapping, but the way the colors change is consistent with the way temperatures change.) Vision is not the only thing, nor is form the only endpoint.

Tobias Gremmler – Visualization of Motion which is widely referenced by academic architects

- Architecture is keen on discussing dynamic content with static media. Here, static media specifically refers to those drawings commonly seen in architectural concept diagrams and theoretical research. It’s like unfolding an ordinary house into countless sections, where the reduction of dimensions leads to a “false richness” in content—it seems rich in information but essentially loses the original characteristics. We often see an architect discussing the dynamic experience of space but never verifying its feasibility or true experience in real-time. Instead, they produce a plethora of concept drawings, telling you frame by frame what happens next, like storyboards in movies. Even when other media, such as programming or game engines, could achieve results and feedback more quickly, many architects are reluctant to move forward, sticking to their traditional drawing tools. The expandability of rules, or the continuity over time. This also leads architects to love to decompose and complicate concepts when explaining them, just as laboriously as describing a movie frame by frame. But the truth is simple; static visual content is entirely insufficient for discussing topics involving precise timing (real-time/interactive). The best way to verify interactive content is to test it against the actual results of the work, not just based on a few polished segments post-processed for human appeal, nor to flatten the content, becoming intoxicated with drawing skills.

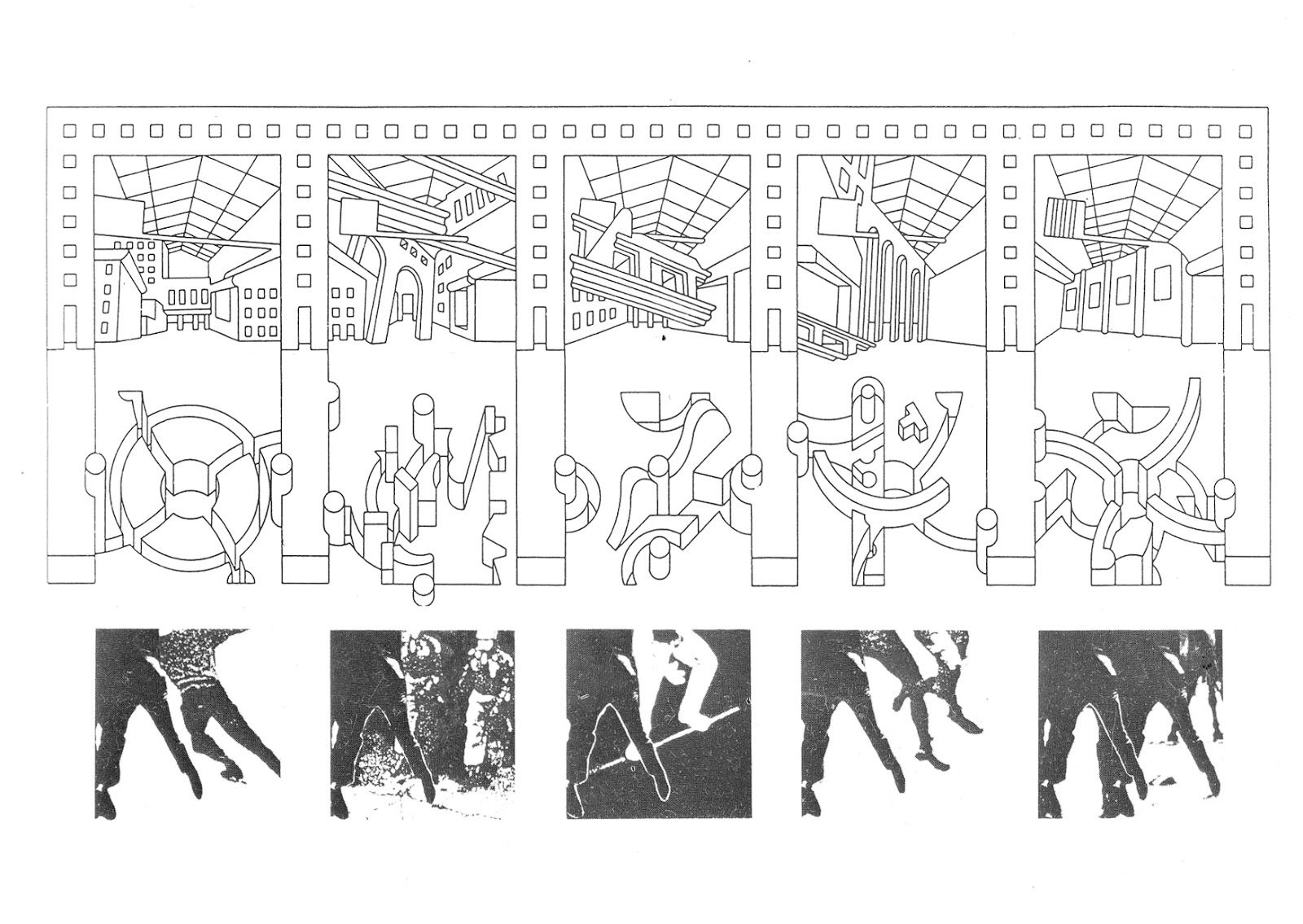

Bernard Tschumi – The Manhattan Transcripts

Exquisite architectural drawings and “dynamic space” – The architect himself said: “It’s not practice nor mere fantasy.” In fact, these drawings only serve the fantasy, and architects need not claim to “serve reality.”

- Architecture is fond of discussing personal experience from a God’s eye view. This God’s eye view broadly refers to the perspectives and ways of experience dictated by architects, such as axonometric, sectional, conceptual diagrams, renderings, or even single-point perspectives. Its antonym is interactive design or game design, where users have the right to decide where to look, where to go, or how to impact the environment. Discussing personal experience from a God’s eye view is like describing how delicious a dish is through an article, as if talking about how spicy the dish is or what its texture is like based on data. Despite the rhetoric being eloquent and the arguments ample, if the audience cannot taste it, they can only applaud the presentation in a fog.

Ville Radieuse – The perpetual utopia of industrial architects

The machinery resulting from the Industrial Revolution still profoundly influences today’s culture. When discussing certain topics like smart cities, architects still scrutinize individual needs within massive simulated systems from a God’s eye view. This mindset, especially when some parametric designers attempt to tackle urban issues, often leads to the neglect of individuals.

To be precise, the above three points have included past architectural masters, with almost none escaping—looking back, there are Daniel Libeskind’s Micromegas, Bernard Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcript, Peter Cook’s Blob City; looking forward, there are “mapping masters” like Stan Allen—they all without exception have proven that architecture as “drawing” is a fact, and their artistic value lies only in “a drawing.” Some may argue that they didn’t have the technology we have today, but the undeniable fact is—the way architecture discusses topics has always aligned with the forefront of current issues, discussing future changes, yet using media that other industries abandoned decades ago. The most striking examples are the big topics for architects: movie storyboards, music scoring, artistic sculptures, choreography drawings… Architecture, as a form of drawing, always focuses on the static image first when discussing any topic. And while all industries are moving forward, architecture is still trying to catch up with the tail ends of others. Just as mentioned above, architecture always tries to “predict” new situations with old methods.

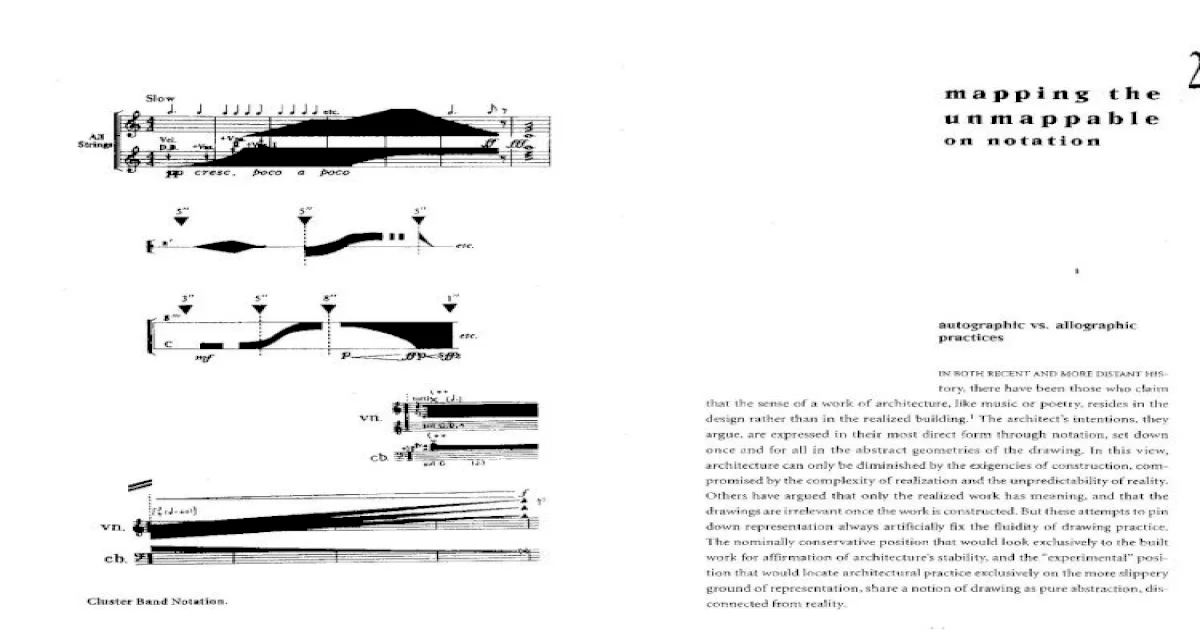

Stan Allen – Mapping the Unmappable

The “mapping” cases that architecture revels in — for most people who don’t use these symbols, they might as well be fanciful tales.

Creating one’s own “language” is an eternal theme in architecture, but when language becomes a tool for communication among a few, it also becomes the deepest divide.

One of the root causes is the mindset constrained by traditional media, that is, the notion that “looking good” and producing “good-looking drawings” is everything. With appealing drawings, architects build their own discourses and persuade others, and what happens afterward is another topic. People’s subjective experiences are even “prejudged” by the architects’ rhetoric, although often these words claim to be “human-centered” or “bottom-up.” However, many times, due to the limitations of media, they are nothing more than attractive but empty promises.

The Future of Spatial Narrative

This article appears to be an academic discussion, but in reality, it is an essay written from a practical perspective. In the author’s view, architecture has always been in an awkward position, neither here nor there, creating obstacles for those who truly want to explore in practice or simply enjoy the process. The architects’ rigid concept of “practice” also imposes the environment’s inertia and pressure on those who really want to dive in and make a difference. The most common example is the dismissal of virtual media and other intangible forms of creative activity by architects as “academic” — “no one will need this when you start working,” “it’s not used in the architecture industry,” “it’s impractical” — without realizing that these creative methods are already mainstream in other industries and systems, with ample funding available. In contrast, the practice of “building houses” is just a part of the whole. Instead, the architects’ most trusted activity of “drawing” often turns into unrealizable fantasies — pure theoretical research is difficult to implement, and there’s no guarantee that one’s creation will win in the construction bids, despite the substantial effort already invested.

The future of architecture is the future of space. What happened to past architectural theories is already history for us; from it, we need to make selections. The limitations of architectural media also cause most people to fall behind the times, limiting our influence in other fields. In my view, architecture feeding back into other industries isn’t limited to constructing a building or using blueprints to describe a possibility. In the future, all innovations and research related to virtual space will require a transformation from architects, and this is closely related to the spatial interaction methods of other industries — interdisciplinary work isn’t just a one-way absorption of information, but a mutual support in both directions.

The future of space and lifestyle requires us to define it with new thinking, and before that, we need to change ourselves with new thinking. An open mindset and the choice of media are the first steps toward external exploration. The static media criticized in this article essentially point to the static, visual, and linear thinking of architects. Forget architecture or architectural design; we need to step out of the mindset we’ve been trained in. Understanding and developing architecture as spatial design in a broader sense is where we should stand — current media have already told us that the future of space isn’t static, not merely visual, and maybe not even physical. Everyone has different tool choices, and although our way of thinking is shaped by tools, it also determines how we use them. “Why bother drawing, just play around” — adaptability is what allows us to extend our influence, and clinging to obsessions isn’t beneficial. In fact, for most architects, what the “ancestors” left isn’t almighty. What we need is just to take a step forward and walk out that door.